An introduction to Merkel Trees

What is a Merkle tee?

A Merkle tree is a data structure which shares some qualities of a binary tree and a distributed hash table.

A Merkle tree is similar to a binary tree, whereby the graph has a branching factor of 2 - each node is expected to have 2 children and end with one root node. A Merkle tree has the following time difficulty properties across all scenario cases.

| Operation | Time difficulty | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Search | O(log n) | Inherted from binary tree |

| Insert | O(log n) | Inherted from binary tree |

| Delete | O(log n) | Inherted from binary tree |

| Space | O(n) | Inherted from binary tree |

The qualities that a Merkle tree inherits from a distributed hash table is that the parent node value is the result of some hashing function using the two child nodes. If either value is changed in the children, then the parent’s resulting value will also be different.

This changed hash will propogate and be used in other hashing functions, resulting in the root being different. This is how the Merkle tree ensures the validity of child nodes values across a large data set.

What are Merkle trees used for?

Merkle trees are often used in decentralised storage, where the goal is to store data over a network of machines.

Because of the hashing quality of a Merkle tree, they are able to hash a large dataset into many fixed sized hashes during tree creation and then are able to pass around a single parent root node, collated of all the previous hashes.

Since Merkle trees can verify a single leaf node inclusion in logarithmic time - less overall data and overhead is needed to prove this inclusion - and this is why Merkle trees are popular in crypto token distributors.

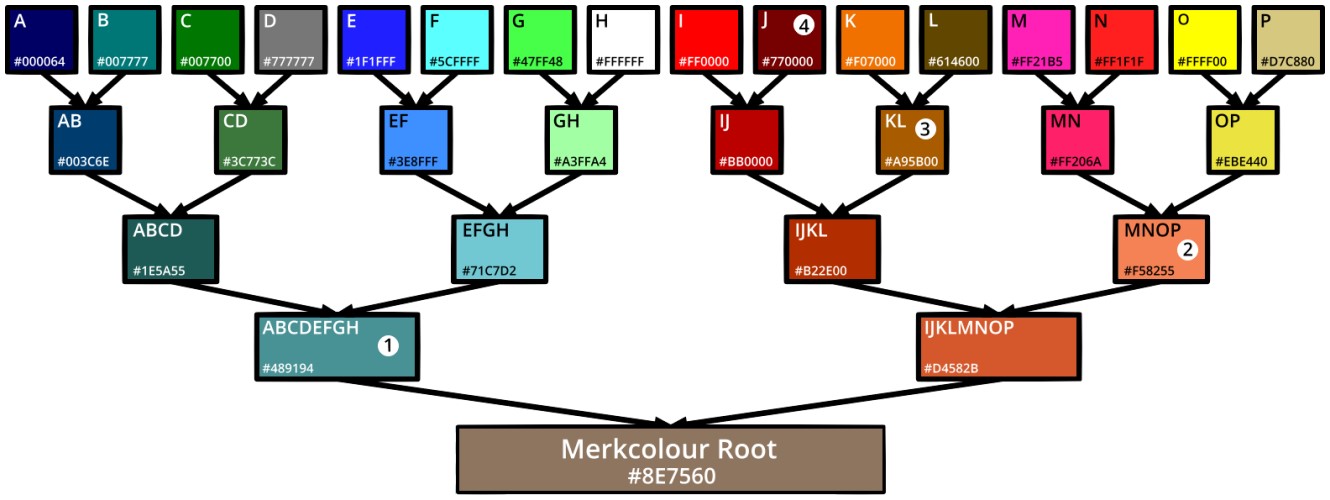

Example of constructing a Merkel tree

When creating a Merkel tree, an inital data is hashed to produce a set of leaf nodes. The leaf nodes are shown as h1 … h4 in the diagram below. The inital leaf data could be :

- Segmented parts of a file

- A list of transactions as a part of a blockchain block

- Other large blobs of user defined data whereby logarithmic time lookups can be done

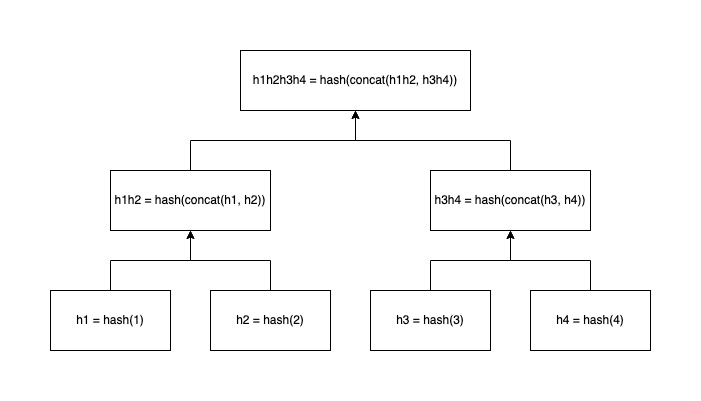

Taking the leaf nodes in pairs like in a binary tree, we create a parent node which is the result of concatenating and hashing the children h1 and h2. This is done until the tree is formed and we are left with one parent root node h1h2h3h4.

A balanced Merkel tree with an even number of leaf nodes.

A balanced Merkel tree with an even number of leaf nodes.

Advantage 1 - Root checksum

The root hash is a derived calculation from the inital leaf data. If a character of data in a leaf node changes then the hash calculated for the leaf will be different, cascading in hash changes down the branches resulting in a different root hash being present. The root is able to be used as a checksum that all of the leaf data are byte-perfect and free from corruption or changes.

If an odd number of input nodes are present at any branch of the tree - then the properties of a binary tree aren’t fulfilled. The Merkel tree should duplicate the orphaned node and hash it with itself. In the below example, the duplicated nodes that are used to balance the tree are highlighted in orange. h5 has no sibling so is duplicated and hashed with itself to create a parent h5h5. h5h5 also has no sibling, so it is duplicated and hashed with itself to create a parent h5h5h5h5. At this branch a sibling exists for h5h5h5 so no duplication is required.

A unbalanced Merkel tree with an odd number of leaf nodes.

A unbalanced Merkel tree with an odd number of leaf nodes.

The naieve way of checking is to generate a new tree from all nodes, in our example these are h1 … h8 and checks that when generating a Merkle tree that the old root and the new root are equal - but this will get computationally expensive to build as the number of leaf nodes grows. The generation of a Merkle tree should only be done once to generate a root, and store the resulting proofs.

Advantage 2 - Logarithmic verification

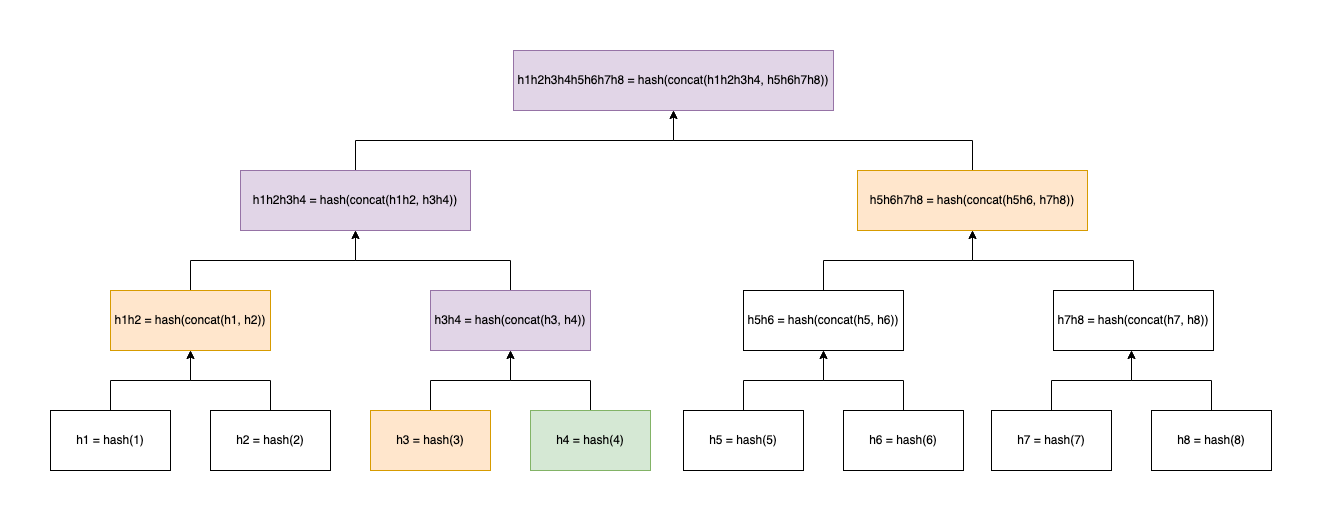

Using the same methodology as before, we create the below tree with 8 nodes.

Note that there are 8 leaf nodes in this example but we only three proofs, three hash calculations and a string comparison for the root are required to do the same amount of computational effort.

It’s this reduction of data input needed to be submitted onchain by the user which is what makes verification so efficent at big N.

Logarithmic searching reduces the computational spend.

Logarithmic searching reduces the computational spend.

Advantage 3 - Gas fees reduced for inserting rewards

Given that we have a Merkle root and we want to submit this onchain - we only need to provide one result hash of a fixed size costing a determinstic amount of gas, compared to adding rows linearly to a contract for the length of our input.

If we had thousands of users to reward or verify, computing and sending a linear amount of gas per operation is not efficent and will quickly bankrupt any funds or treasury you have to distribute these.

The below example shows the difference between the two models. The main pattern which is being used by these contracts are push vs pull. Do you push tokens to your user at a cost of gas, or do you make your users pull the rewards and offsetting some of that cost to them?

The current ZRC-2 and MerkleDistributor contracts model rewarding users with a fungible token with a Merkle tree.

Transfering has been a popular mechanism for airdrops but is wildly inefficent, naievely distributing tokens by iterating a collection in linear time and sending funds from A to B, costing the developer an gas amount linear to the amount of users in the collection.

The only upside for airdropping directly is that your users do not have to submit a transaction, which might be useful if your users don’t own any crypto or are lazy and won’t claim the reward, but the problem remains they will have no funds to interact with whatever you reward them with as they will be unable to pay the gas fees.

100 users

| Blockchain operation | Avg op cost (ZIL)* | Ops required | Total cost (ZIL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admin Merkle Root Submit | 0.774 | 1 | 0.774 |

| User Merkle Root Claim | 4.634* | 1 | 4.634* |

| Admin Transfer A -> B | 3/6* | 100 | 300/600* |

1000 users

| Blockchain operation | Avg op cost (ZIL)* | Ops required | Total cost (ZIL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admin Merkle Root Submit | 0.774 | 1 | 0.774 |

| User Merkle Root Claim | 6.113* | 1 | 6.113* |

| Admin Transfer A -> B | 3/6* | 1000 | 3000/6000* |

*Variable depending on input byte length.

The conclusion we can draw from analysing the two distribution mechanisms is that the pull strategy is efficent as only one root is being submitted onchain, and it’s also negligable to ask to users to submit a transaction that costs a small amount of gas. Whereas the push mechanism can quickly scale out of control for large N.

Token Distributors

An example of when a Merkle tree is best used is in cryptocurrency token distributors. We can ensure unbiased processing of the computation and exeuction of rewards using smart contracts.

There are several reward concepts in crypto which require funds to be sent to users, either for participating in liquidity pools, defi or just holding an NFT. Since the Merkle contract just proves or disproves that a users proof is correct, you can enable mints, transfers and practically anything else you’d want to gatekeep.

One of the vectors of attack with a Merkle tree is the proof availability. If an attacker can disrupt where the proofs are being distributed from then users will be unable to claim their tokens. Decentralised storage mitigates nearly all of this risk. This isn’t such a problem for smaller projects, but larger projects can be majorly distrupted.

Introduction to Merkle trees on Zilliqa

Problem Statement - Reward users in LP with a fungible token

1 | GIVEN some users are providing liquidity to a DEX where the state is a tuple of \<account, amount\> |

This scenario is very common and can be modified to fit other scenarios such as holding a particular NFT or airdropping fungible tokens or NFTs.

We do need to take note of the rewarding timeframe. Too quickly and users will need to submit several transactions which may not be gas efficent for a small amount of tokens each time. Too long and your users will be annoyed at the frequency but will have a larger amount of tokens sent in a single transaction - which could have a negative impact on price performance. Targeting rewards for once a week seems to be the sweet spot which users don’t mind, all depends on how much gas is used and how much this costs on your chain of choice.

We want to take a snapshot of contract state every hour to track the state changes over the period of a week.

1 | (1 snapshot * 24 hours) * 7 days = 168 snapshots |

We’ll need to collect the LP data for each user and how much they have at the time of the snapshot.

We can then average the leafs into one final result set. From this result set we will have the average amount deposited over that period and how much of a percentage they own.

We will have a fixed amount of tokens we want to reward over this period, we can calculate how many tokens each user should get from knowing their percentage owned at each epoch.

Once we’ve summed and averaged all of the amounts, we’re left with a data structure like the below.

1 | const b16Leaves = |

From here, we can generate a Merkle Tree which will contain all of the proof data and Merkle root.

1 | const tree = generateTreeforBase16(b16Leaves) |

1 | { |

The MerkleDistributor allows the Admin to post new roots to it. An example of this.

MerkleDistributor allows users to submit proofs with their inital dataset to check if the derived root is equal - it also let’s them batch multiple claims together. An example of this. (Notice the tokens being newly minted from the null address to the users wallet)

Once claimed, the Distributor stores a record in the state of the claimed leaf, so that repeated claims can be detected and identified to be hidden on the web client.

Summary

Merkle trees are becoming more common to see as developers don’t wish to pay for unnecessary gas costs, especially on chains where the native crypto is expensive.

The technicalities of Merkle trees can be easily hidden by web clients whereby they know nothing about the snapshots or the proofs they need to pass - it can be as simple as showing reward rows.